Ehsan

O

Ehsan

One heard about the recent social upheavals in Afghanistan in the media. Everyone who lived in Dubai had some connection to its neighbouring countries. As I grasped the grim news coming from that region, I contemplated a short-lived friendship in my first year in Dubai.

In 1977, I worked in the Inter-Continental Hotel, the only five-star hotel in the desert city. Dubai was slowly transforming into a burgeoning regional hub connecting the East and the West. Wealthy business people who could afford the hotel’s exorbitant room fees stayed there while conducting trade deals. The only way of communicating formally was through telex. I was at the forefront of serving the hotel guests needing these critical services, meeting many people in business in the process.

A big made businessman in his sixties was a regular customer who frequently used telex services. His name was Mr Hosseini. He tipped me generously and was always accompanied by a tall, handsome lad of between eighteen and nineteen, his son. The young lad often came to the telex department alone to use telex services on his father’s behalf. The young man spoke eloquent English, in contrast to his father.

Gradually and within a short period, I became acquittance with the young man.

His name was Ehsan. What struck me was Ehsan’s sharp features, straight nose, and jet-black hair. He was always smartly dressed in white shirts, long, crisply-fit jeans, and expensive leather boots.

Ehsan kept on turning up regularly at my office. Sometimes to send a telex or to check incoming messages. Often, he’d come to strike up a conversation. He’d lean over the countertop and talk to me between my work. We spoke, standing on opposite sides of the counter. I was interested in learning about Ehsan, his culture, origin, and life. A bit of cultural information exchange was going on between the two of us.

Ehsan was Iranian. He studied in Geneva but lived in Paris, where his father had a second home. Ehsan was the only child. His father wanted Ehsan to learn the family business. His father wanted him to be with him in Dubai during Europe’s summer break. Ehsan was multilingual. He could speak English, French and Persian.

At work, if I was free, I sat alone in the office, waiting for the next guest. Ehsan turned up at all sorts of hours to chat. It was a great way to kill our mutual boredom on hot summer days in Dubai. His visits became a routine. I addressed him as Master Hosseini, ‘master’ being the junior version of mister back when hotel workers addressed their guests as mister or madam. Ehsan was too young to be addressed as Mister. “Denzil, please don’t call me Master Hosseini; call me Ehsan”, was Ehsan’s response.

Our friendship had settled on a first-name basis, Ehsan invited me to his room. As a hotel worker, I should not have visited guests’ rooms unless I worked in room service or the housekeeping department. I took on his invitation anyway. To my surprise, Ehsan had a room for himself on the hotel's ninth floor. The room was large with a TV. His father occupied the adjoining room, but a door linked both rooms. Now, it dawned on me that Ehsan’s father was wealthy enough to be able to afford two rooms one for him and one for his son.

Our friendship progressed. Some days after I finished work, I joined Ehsan to walk along the waterfront. We walked until sunset, passing the floating cruise ship, dhows and the ‘abra’ boats in Dubai creek. We stopped in the Deira markets and ate at cheap roadside eateries, something Ehsan had never done in Dubai. I introduced him to crispy Indian parathas and chilly curries.

On another walk along the creek, Ehsan wanted to smoke a cigarette. I readily offered him one from my Rothmans pack. We smoked sitting by the waterway. Ehsan started puffing and coughing as a result of the smoke. He felt faintish. Things were not going well for him. Until then, I did not know it was the first time he smoked. We walked back to the hotel and I went to his room to settle him.

Ehsan started feeling better. I was getting ready to leave his room. Quite unexpectedly, his father, wrapped in a colourful robe, walked in from the adjoining room using the common door. I felt awkward and guilty for Ehsan’s previous predicament. But Ehsan tactfully diffused the situation by speaking to his father in Persian. Fortunately, his father did not suspect anything to do with smoking or my involvement in it. Greeting me in English in a strong Persian accent, “Hello young man, you are the smart telex operator; what is your name?” asked Mr Hosseini. I politely responded, “I am Denzil, I am happy to meet you”. He offered to order tea from room service. I respectfully declined. Hosseini senior returned to his room, leaving us both alone. I watched an episode of Charlie’s Angels with Ehsan on TV and left soon after for my hotel accommodation quarters.

Sometimes, Ehsan dined at the hotel’s coffee shop with his father. His father entertained businessmen, Arabs and men in Western attire, possibly to conduct business deals. Ehsan dressed in a smart suit for these occasions. I could see them straight opposite my office in the coffee shop. When Ehsan saw me, he’d interrupt their meal, walk up to greet me and exchange a few kind words.

Ehsan and I continued to hang out between work and some days after work. Luckily Ehsan never asked to smoke after that. We walked in the Iranian quarters in Deira markets, Ehsan comfortably mixing with the retail workers wearing Iranian baggy pants. Ehsan took me to the Jean shops selling American jeans, also run by Iranian merchants. He helped me pick and fit a pair of black corduroy pants made and favoured by lads. It was seventy Dirhams, a sum I did not have in my wallet. Ehsan opened his wallet generously without any second thoughts and paid for it. To my embarrassment, Ehsan never took my money for the jeans. It was his unintentional gift. The jeans were to become a much-loved pair for years and lasted a lifetime. On another day, while touring electronic shops with Ehsan, I bought my first digital watch, a Casio, a modern-day smartwatch.

“Haal-e Shoma” is the only Farsi phrase I learned from Ehsan. It meant How you are?. He tried to teach me more Farsi keywords. Most of them were tongue twisters which I failed to grasp despite Ehsan’s best efforts.

Hotel guests had a habit of leaving their books behind after reading them. When I finished a used book by Henry Miller about free life in Paris, Ehsan was the first to borrow it. It was a banned book in some countries for its explicit content. On another day, while chatting, Feroz Khan, a famous Indian movie idol, came to the telex department. I could not believe I was in front of a great Indian movie star. I was Khan’s fan, having watched his movie, ‘Safar” in my boyhood days in Sri Lanka. “You are very popular in my country, Sri Lanka, Mr Khan”, I quipped. Feroz Khan was gracious enough to speak to us, two besotted fans, without pride. While talking to him, Ehsan and I were mesmerised by Khan’s e presence and charisma. Feroz Khan himself had Persian ancestry, he told us.

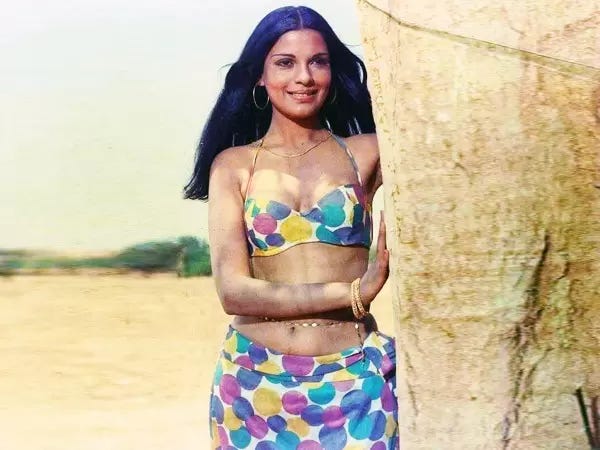

The coffee shop across from my office in the hotel was a meeting ground for the region’s rich and famous. Another day, I saw Zeenat Aman, the favourite Indian celebrity and actress, in the coffee shop. She was wearing an elegant white lace dress. Zeenat was my favourite and the most beautiful actress in Asia. She was dining with her beau. I could not believe what I was seeing in front of me. Excited, I called Ehsan into his room. Ehsan hurriedly came down. We two, Zeenat’s fans, pretended to be talking business and did not take our eyes off Zeenat. We were damn lucky to get a glimpse of Zeenat Aman, a legend in Indian cinema.

In August 1977, I was offered a job at the Chartered Bank. From then, with two jobs, one in the bank and one at the hotel, during the changeover period of one month, I did a night shift in the hotel. Some evenings Ehsan would turn up to see me for a chat. There was hardly any work on the evening shift; we talked a lot about his life in Iran, France and Switzerland and my own in Sri Lanka and now in Dubai. Ehsan was keen to visit Sri Lanka with me on holiday.

I left the hotel finally in September of that year.

In December, Ehsan visited me at the bank in Bur Dubai. With him was a gift, a Pierre Cardin tie pin bought from France for me. After work, we went out for a stroll on Al Fahidi Street. We walked into various shops and electronic shops in glittering bur Dubai. He was leaving for Tehran with his father that weekend. I felt deeply grateful that he had considered me a close friend to bring me a gift. We exchanged our addresses and promised to write to each other. A week later, I left for Sri Lanka to see my parents, my first trip back after I left my home some eight months ago.

We exchanged occasional letters between Geneva and Dubai.

Next summer, I had a surprise visitor at the bank. It was Ehsan. I was delighted to see him again. After work, I took off with Ehsan, taking a taxi to Jumeirah beach. It was a spur-of-the-moment decision, an impromptu action. We did not come prepared to the beach, let alone swim. We did not have towels or swimmers. Stripped to our underwear, we swam in the blue sea. There were no towels to wipe when we finished. Fortunately, the Dubai sun was so hot in summer, even at 7 pm, that the water evaporated rapidly. In no time, we were dry.

We sat on the beach and talked, looking over the vast Hormuz sea before us, pointing us towards Iran. I, about my work life in the bank and plans for my future. Ehsan talked about his final year in college and social unrest in his homeland, Iran. His father was finding it hard to do business in Iran. I read about Iran’s troubles in the recently launched Khaleej Times and the Economist. Opposition to the rule of the Shah was mounting in Iran. There were many violent protests. Ehsan nor I was mature enough to understand what the future held for Iran. Liberal Iranians like Ehsan’s family were taking the brunt of this social instability, I figured later.

We took a taxi and returned to the Inter-Continental Plaza, where he was now staying with his father. We parted company, unaware that our part of the world was evolving rapidly.

I wrote to Ehsan a few months after that in Geneva. There was no reply. There were no forwarding addresses. Back in the day, one relied on snail mail. Mobile phones and social media were to evolve a few decades later. A second letter also evoked no reply.

The Iranian situation worsened after my last meeting with Ehsan at Jumeirah beach. The Shah of Iran was overthrown. An Islamic regime was installed. There was chaos in Iran, political and social instability, assassinations, bombs, executions, and hostage crises. Iranians lost most of their freedoms and their place in the world. I am sure that Iran was no place for Ehsan.

I have not heard from Ehsan since then. Forty-five odd years later, I have not been able to find him on social media channels, despite some frantic searches. When I see news about Iran in the media today, whether it is about sanctions, nuclear ambitions, an Islamic caliphate, or public executions, my mind immediately returns to Ehsan.

I often think about where Ehsan could be today. Is he safe somewhere in Europe? Is he a grandfather like me now?

It would be lovely to reconnect with him and exchange how two accidental friends' lives evolved since those sunny days in Dubai in the seventies.

Related Links:

Denzil’s first impressions of Dubai

Subscribe to my stories https://djayasi.medium.com/subscribe

Images belong to the original copyright owners.

Comments

Post a Comment