Doctor Doctor

Doctor Doctor

Memories of medical care in my early years

Asa toddler, I contracted whooping cough, a deadly disease of that time. My mother went through a lot of anxiety until I got better. She was so pleased with the doctor who treated me that he became our family doctor. As a two-year-old, I don’t remember a thing about that trying time. It must have shaken my mother so much; she thought my survival was a miracle. She never failed to remind me of that fact growing up.

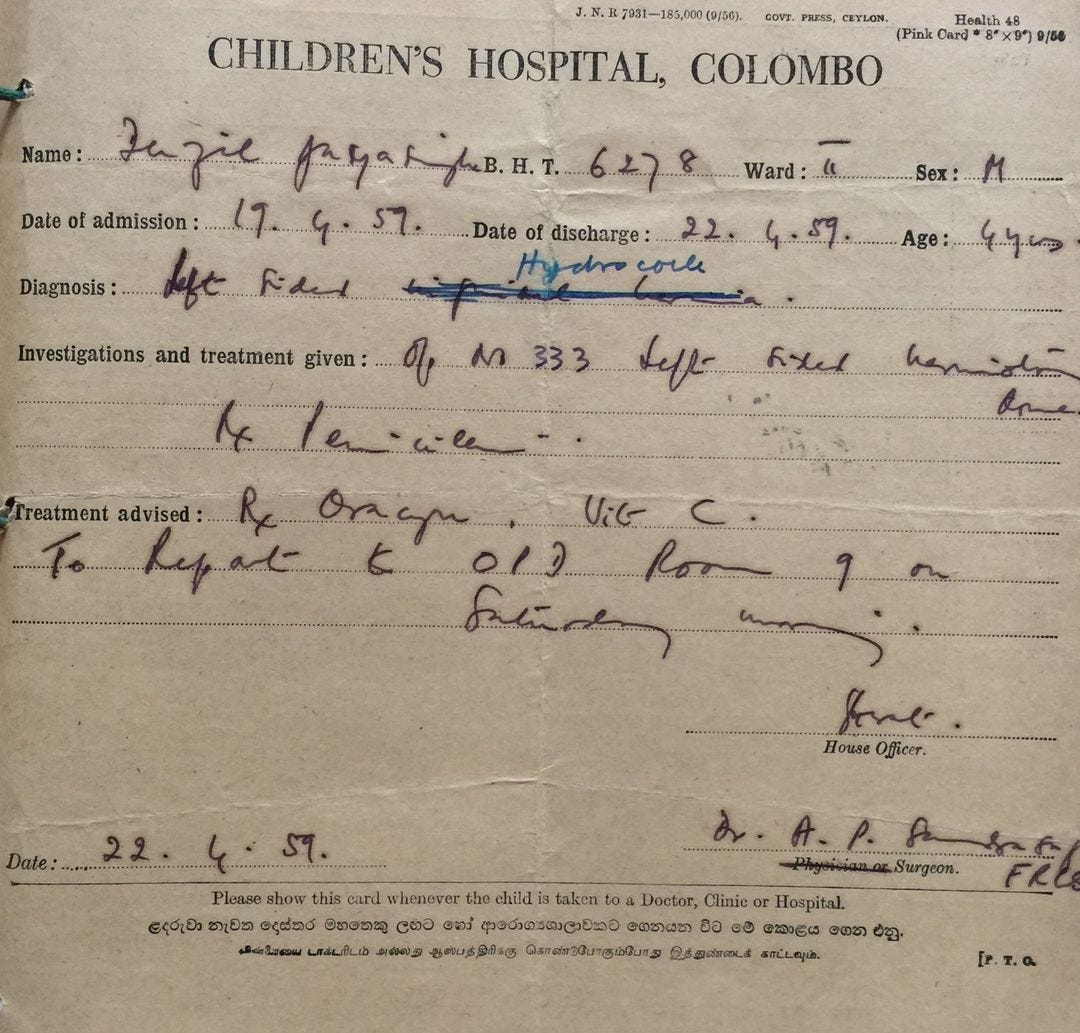

At four years, I was operated on for hydrocele at Lady Ridgeway Children’s Hospital in Colombo. During my entire stay, my mother stayed with me at the hospital, sleeping nearby. I have great memories in the hospital, caring nurses and frequent visits from my grandfather, Lewis. I loved his visits, his fancy stories sitting on my bed. When the hospital discharged me after four days, my grandfather carried me to his car. Back home, I was not allowed to wear pants until I healed. That was embarrassing.

The discharge notice below says that the diagnosis was hydrocele. Underneath the surgeon’s writing is, left-sided inguinal hernia, which has been struck out. Whatever it was, I came out good, except for a tiny scar that is with me today.

The home cure for respiratory infection was an age-old treatment. My mother and grandmother covered me on a white sheet. I sat under it, inhaling the vapour from a hot earthen pot. Another home remedy was drinks made from boiled coriander seeds. If the fever persisted, visiting the family doctor was the next step.

Visits to the doctor were by a hired car. The family doctor, Dr V T Perera, ordered a sour mixture from the dispensary adjoining his practice. A tablespoon three times a day with its awful bitter taste was torture to a little kid. One quick gulp and closing my nose was the only way to minimise my agony.

My mother measured her children’s temperature with a thermometer under the tongues. One had to hold the glass device inside the mouth between teeth carefully. It was an art. There was no rice and curry while suffering from the flu. Instead, it was rice gruel, toast, a cream cracker, and orange barley on a lucky day.

Every school holiday, a visit to the doctor for bowel treatment was a must. One must always be ready to run to the toilet for that magic moment. I hated that cure.

Kadayamma, my grandmother, was slim, active and healthy for her age. She relied on Ayurvedic treatments and did not believe in Western medicine for aches and pains. I was her willing companion when she visited her Ayurvedic doctor. The treatments were native herbal mixtures.

Kadayamma’s generation, like many that were brought up in the early half of the last century, were prejudiced against Western treatments. For wounds, she drank a veni-val drink, an ayurvedic medicine to prevent Tetanus. In that period when dental treatment was rare, a clove was stuffed into the tooth cavity for toothaches.

Oils played an important part back then. The best-known and most prominent oil muscle ache was Siddhartha oil. Everyone applied coconut oil to their hair, including women and children.

My parents relied on Western medicine, and their association with Ayurvedic medicines was limited to the occasional herbal drink and oils.

When I was about eleven, my father was operated on for a hernia at the general hospital in Colombo. When I visited him with my mother, he did not get up from his bed. His facial expressions showed that he was in considerable pain. I was upset to see my father in that condition, helpless. My mother lovingly fed him soup from home while I stood beside him. He was delighted to see me and enquired about my siblings, who were too small for a hospital visit.

One had to navigate through several buildings and passages to get to my father’s ward, 66, on the third floor of a huge building. It was the largest hospital in Sri Lanka. The nurses in their white uniforms, the strong smells of medicine in the hospital wards, the patients on beds, the visitors who had come to see them, the doctors in their white overalls, and the hospital attendants who saw to the patient’s chores and cleaning; all of them were novel experiences for this young boy. The air in the wards was filled with a strange smell: ammonia disinfectant.

After a few days, my father returned home. Recuperation was hard for him; he walked slowly, shouting in pain. To ease his plight, I carried buckets of water to the toilet for him. I carried water for him to bathe when my mother was busy.

Now that I was older, I had to fetch the hired car when my sister and brother were sick. The regular driver from our neighbourhood charged five rupees for the return trip to see the doctor. He patiently waited in the car park until we finished. He was a kind man.

Three years later, my kid brother, now seven, had an accident at home. He hurt his eye playing with my sister. My father was away at work, and I was in boarding school. By the time my mother could take him to the eye hospital, it was too late for my brother. The damage to the eye had been extensive. That was a traumatic period for my parents.

Three operations later, spanning a few years of my brother’s school life, the doctors could not salvage his vision in the right eye. My parents blamed themselves for not acting fast enough. Young as I was, I blamed myself, for I was not there to help my mother in her time of need. But that was life back then. With limited mobility and access to hospital care was not that easy.

When I was sixteen, a few black spots appeared on my face under my left eye. I also developed warts on my right upper wrist and knee. My father, who quickly noticed these things, took me to the hospital. Under a local anaesthetic, both the black spots and warts were laser-removed.

But, in an age when hormones fight back, dreaded warts reappeared about a month later. My father did not relent. Another visit to the hospital with him was the next step. This time, the treatment was complex, unheard of and novel. I was taken to day surgery while my father stood outside the ward. The white-wearing surgeons asked me to remove my pants. I was perplexed but obeyed despite embarrassment in front of female doctors and nurses. Me lying on a steel plate; they removed the biggest wart on my knee and buried it in my upper thigh through a small incision. Under anesthetic, of course. Thank God.

After that peculiar treatment, a huge plaster covered my thigh over the sutures. My father escorted me out of the hospital ward, dropping me home by bus, me limping all the way.

I was not allowed to shower for a few days should the new wound with fresh stitches get infected. It was my father who, after his work day, lovingly gave me dry baths with a wet cloth until I could shower on my own.

The experiment was worth the sacrifice. In a matter of days, the sutures disappeared. The dreadful black spots and warts disappeared for good. Gone forever! I was a clean boy with no scars. I thought it was a medical miracle. I still think so.

I did not notice this, but my father noticed my left ankle was slightly swollen while washing. My father was always one to take action immediately; another visit to the doctor and a specialist ensued. After several hospital visits and many X-rays, it turned out there was nothing wrong with my ankle. They advised my father that it was a slight abnormality that I would have to live with my whole life. Those doctors were right. Even today, my left ankle bone looks as if it has a slight swell. I have had no issues with it.

My other grandmother, my mother’s mother, was cared for by my mother, at great odds with her. As a schoolboy, I fetched medicines regularly for my grandmother from the hospital. I did that happily for my mother.

Every day after breakfast, my father poured a tablespoon of ‘Haliborange’, a sweet nutritional supplement. It was a must before heading to school.

My father’s emergency

The biggest medical emergency in our family happened when I was twenty. My father suffered a heart attack at a relative’s faraway home. He survived and was taken to a nearby hospital by our relatives. That night, on hearing the news, my mother was anxious and hardly slept. I was too naive to know the seriousness of what happened to my father. The next morning, my mother took off to see him at the hospital.

My mother travelled daily to see t ten days, trekking more than 110 kilometres on the round trip. Travelling on three rickety bus routes each way must have been tiring. In the evenings, she made vegetable soups for my father to be taken on the trip. This she did diligently and faithfully until my father came home after those demanding ten days.

It turned out that my father has had not only heart disease but diabetes, pressure, and high levels of cholesterol. These diagnoses came out during the tests during his hospital recovery. My mother, the fixer of things, sprung into action. She put him on a strict diet, boiled vegetables with no red meats or sugar.

My father took insulin injections every day to treat his blood sugar levels. He was careful not to do that in front of his children. Accidentally, I saw him inserting the needle into his thigh. Young as I was, it was an awful scene that has edged in my memory forever. He never complained and did forego these inconveniences for the family.

My mother was determined to make my father healthy again. She never relented on his diet. I felt bad eating tasty Sri Lankan foods cooked with spices and coconut milk in front of my father. A few times, I pleaded with my mother to allow him to have a normal meal occasionally. My father liked his food, and it must have been a terrible sacrifice for him to forego his favourites.

But my mother’s resolve worked, and my father recovered well to be active in no time. In record time, my father lost weight and became a slim man. He was in his late forties at the time.

His experience at the threshold of death became a decisive moment in my young life. I determined that I would take care of my body and be healthy. I am fortunate to have not inherited any of my father's diseases. I have tried to be physically and mentally healthy, remaining slim all my life and will do so for the remainder.

In contrast to my experiences, my kids in Australia have had far superior medical treatments. The care they received has been exemplary, nothing like back in Sri Lanka. I have had my share of anguish when they were in hospitals for tonsils, fractures from sporting accidents, falls, and wisdom teeth. But all those experiences turned out to be good.

Subscribe to my stories https://djayasi.medium.com/subscribe.

Similar stories:-

Comments

Post a Comment