The Ironed Fabric of Dalugama

This is a poignant story set in 1967 Ceylon, focusing on a humble laundry run by two brothers, Victor and Piyadasa. The narrative revolves around a young boy who is captivated by the meticulous work of the laundry brothers, especially Piyadasa, who uses a traditional charcoal-heated iron to press clothes. While the brothers worry about the future of their craft, the boy finds solace and meaning in the personal touch and care they provide, which machines cannot replicate. The story emphasizes the importance of tradition, craftsmanship, and human connection in a world undergoing rapid change. It uses the metaphor of the ironing process to represent the transformation and shaping of a community, highlighting the enduring value of human touch and the power of personal connections in a changing world.

Inthe languid sleepy village of Dalugama, just seven miles northeast of Colombo, life moved at the pace of the warm breeze that rustled through the coconut palms. It was 1967 and Ceylon was still adjusting to its newfound independence, much like young Boy was adjusting to the cusp of adolescence.

Past Lal’s water well, where children gathered in the afternoons to splash and chatter, stood a humble laundry. Its doors and counter were fashioned from weathered wooden planks, their grain telling silent stories of countless monsoons. This was no modern laundrette like those emerging in faraway Australia. No, this was a place where tradition and necessity intertwined like the very fibres of the garments it tended.

The laundry was the domain of two brothers, Victor and Piyadasa, who had journeyed north from their village in the deep south of the island. They were as different as the two seasons of Ceylon — Victor sturdy and deliberate like the monsoon, Piyadasa lithe and quick like the dry winds that followed.

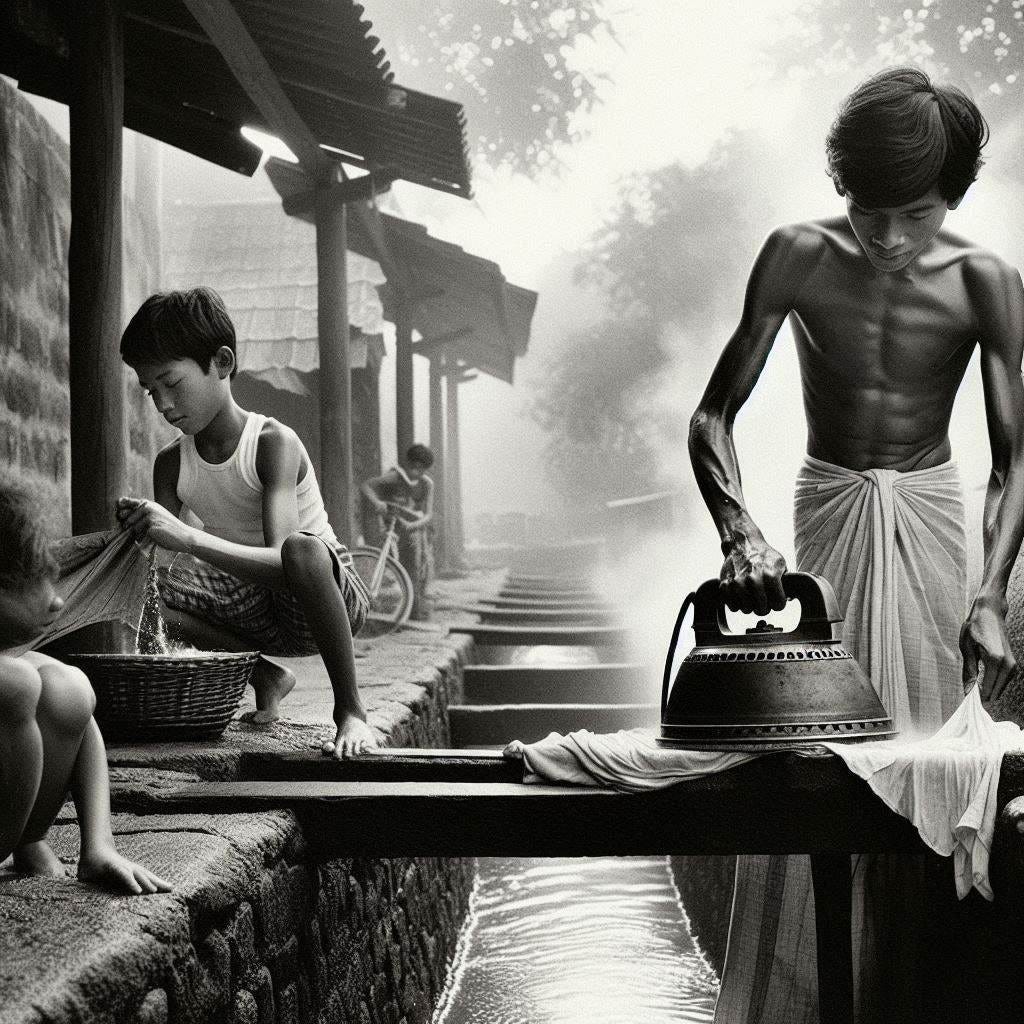

Victor, the elder, spent his days by the narrow waterway that snaked behind a bridge. His powerful arms worked tirelessly, plunging clothes into the cool stream, his movements a rhythmic dance learned over years of practice. The sound of wet fabric slapping against stone mingled with the occasional grunt of exertion, creating a steady backbeat to the neighbourhood’s daily symphony.

Piyadasa, younger and more outgoing, manned the front of the shop. From dawn to dusk, he stood before the ironing board, his lean frame moving with the grace of a temple dancer as he transformed rumpled cloth into crisp perfection. His tool of trade was no ordinary iron. It was a behemoth of metal, hissing and steaming like some dragon of domestic duty. Inside its cavity burned red charcoal, lending a faint smoky scent to the air that permeated the entire street.

Both brothers wore the traditional sarong, wrapped around their waists and falling to their knees in neat folds. The white cloth stood in stark contrast to their dark, sun-bronzed skin, a visual testament to their southern heritage. They worked bare-chested, the tropical heat making any additional clothing an unnecessary burden.

It was to this establishment that twelve-year-old Boy found himself drawn, time and time again. He would linger by the counter, ostensibly waiting for his father’s clothes, but in truth, he was captivated by the alchemy that transpired within.

Boy’s father, a mid-level government official, insisted on a certain standard of appearance. His khaki trousers were a uniform of sorts, a symbol of respectability in a newly independent nation still finding its footing. When these pants emerged from Piyadasa’s ministrations, they were nothing short of a miracle to young Boy.

He loved to run his small hands over the fabric, marvelling at its transformation. Where once had been a crumpled, lifeless heap, there now stood a creation of geometric perfection. The creases were knife-sharp, the pleats precise as a mathematics equation. And oh, the warmth! It was as if the very essence of the sun had been captured and woven into the fibres.

“Come, little one,” Piyadasa would say, his eyes crinkling with amusement. “Feel the magic of the iron.”

Boy needed no second invitation. He would press his palms against the freshly pressed trousers, relishing the crisp texture and residual heat. It was a tactile pleasure that never failed to delight him, a small joy in a world that was rapidly changing around him.

As Ceylon slowly shed its colonial past, embracing a new identity of an independent nation, the laundry remained a constant. It was a bridge between the old ways and the new, a place where ancient craft met the demands of a modernizing society.

One sweltering afternoon, as the cicadas droned their endless song, Boy arrived at the laundry to find Piyadasa in an unusually pensive mood. The customary smile was absent from his face, replaced by a furrowed brow and distant eyes.

“What troubles you, Uncle?” Boy asked for he had come to regard the brothers with the familiar affection reserved for family.

Piyadasa sighed, setting down his iron. “Ah, Boy. The world is changing, you see. In Colombo, they’re opening a new kind of laundry. Machines that wash and dry clothes without a human hand to guide them. What will become of us, I wonder?”

Boy frowned, trying to imagine such a place. It seemed cold, impersonal. “But Uncle, can a machine press clothes like you do? Can it make my father’s trousers warm and perfect?”

A slow smile spread across Piyadasa’s face. “Perhaps not, little one. Perhaps not.”

As if to prove his point, he picked up a shirt from the pile beside him. With practised ease, he shook it out, laid it on the ironing board, and began his work. Boy watched, mesmerised as always by the transformation taking place before his eyes.

The iron glided over the fabric, steam rising in soft puffs. Piyadasa’s hands moved with confidence born of years of experience, knowing just how much pressure to apply, just where to linger for a stubborn wrinkle. This was no mechanical process; it was art.

“You see, Boy,” Piyadasa said as he worked, “this is more than just making clothes neat. This is about care. About paying attention to the little things that make life better. A well-pressed shirt can give a man confidence. It can make him stand a little straighter, and smile a little easier. Can a machine understand that?”

Boy shook his head emphatically. “Never, Uncle. Never.”

As the weeks passed, Boy noticed more and more of the neighbourhood residents bringing their clothes to the brothers. It seemed he wasn’t the only one who appreciated the personal touch, the attention to detail that no machine could replicate.

The laundry became more than just a place of business. It was a gathering spot, a place where news was exchanged, where joys were shared and sorrows comforted. Victor and Piyadasa knew every customer by name, and knew their preferences, and their stories.

And always, there was young Boy, soaking it all in. He watched as the brothers navigated the changing tides of their world with grace and resilience. He learned the value of hard work, of taking pride in one’s craft, no matter how humble it might seem to others.

Years later, long after Ceylon had fully embraced its identity as Sri Lanka, long after electric irons had replaced the charcoal-burning giants of his youth, Boy would still remember the laundry by Lal’s well. He would recall the smell of steam and smoky charcoal, the sight of white sarongs against dark skin, and the feeling of his father’s perfectly pressed trousers warm beneath his small hands.

And he would smile, grateful for the lessons learned in that humble place — lessons of dignity, of perseverance, of finding magic in the everyday. For in the end, it was not just clothes that were transformed in that little laundry, but the very fabric of a community pressed and shaped by the caring hands of two brothers from the South.

Comments

Post a Comment