Sunlit Stillness

Sunlit Stillness

A Visit to Wilson Uncle’s

The Saturday sun bore down heavily, not with the fierce urgency of summer but with the unhurried weight of a day that had already resigned itself to stillness. Denzil wheeled his bicycle to a halt and leaned it carefully against the concrete steps of Wilson Uncle’s verandah. The steps, pitted and chipped, seemed as weary as the old house behind them — a house that exhaled the scent of old walls and quiet dampness, of memories sealed into plaster and timber.

He called out softly, “Uncle, it’s me. I’ve come to visit. Where are your magazines?”

From somewhere inside, beyond the shadows that clung to the high ceilings and cluttered corners, came a faint, delayed “Oh,” as though Uncle Wilson had just been pulled back from a conversation with his thoughts, or perhaps from a silent dialogue with his past — things left unsaid, stories never fully finished.

Denzil shifted slightly, the bicycle’s stand releasing a rusty creak. “People… they speak well of your writing, Uncle,” he said, the words finding their way out with the uncertain sincerity of someone unused to giving compliments aloud, but meaning them nonetheless.

Before a reply could form, Neeta Aunty appeared at the doorway. She stood there, tall, thin, the fabric of her frock slipping over her bones as if even cloth had forgotten how to hold onto her beautiful frame. Her eyes, sharp despite the softness time had etched into them, studied Denzil with an affection that was both familiar and enduring.

Sunlight seeped through the roof. “Oh, Putha,” she said, her voice low and grainy, textured by years of speaking gently and holding back more than she gave. “You’ve grown — almost caught up to me now.” She placed a hand on his shoulder, her skin paper-thin, the gesture rich with remembered affection and the quiet assessment of one who had watched him grow at irregular intervals. “And your father, your mother — are they keeping well?” Her words lingered in the warm stillness, like dust drifting in the shafts of sunlight from the roof.

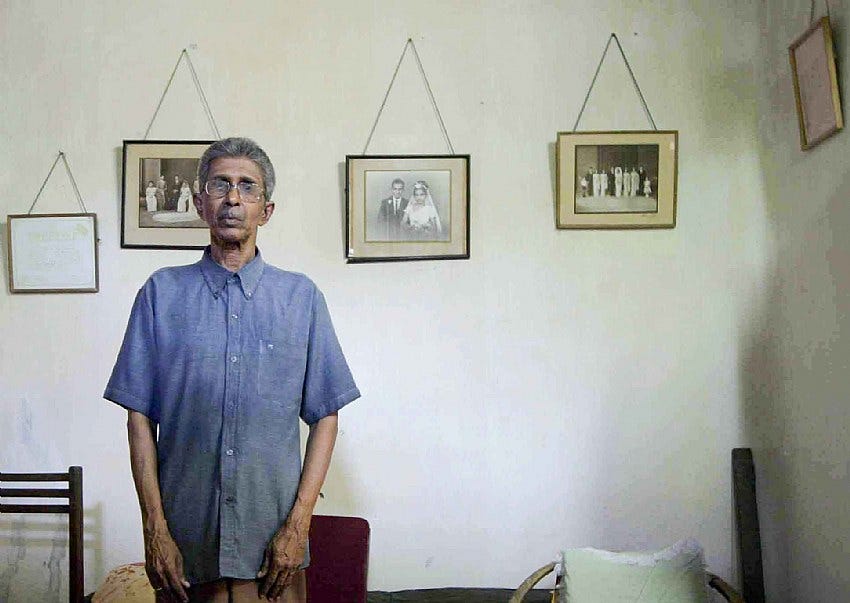

Denzil nodded. His eyes flicked toward the small wooden cupboard in the corner of the sitting room. On top of it sat a neat stack of SRI magazines. Above it, framed photographs lined the wall — Wilson Uncle and Neeta Aunty, caught in time during birthdays and anniversaries, and off to the side, slightly tilted, the faded image of their wedding day. Eight years ago, that photo was taken. Eight years already.

He remembered coming to this house as a child — back then, Wilson’s father still sat on the verandah, fingers curled expertly around strips of cane, weaving chair seats with the patience of someone who understood the value of repair. In later years, the weaving gave way to another occupation: marriage broker. It had always struck Denzil as ironic that a man settled into old age with a wife and a house should spend his time finding companions for others. Denzil remembered him arriving at their home with a stack of proposals, all intended for Denzil’s unmarried uncle. But now, Wilson Uncle and Neeta Aunty lived alone, childless except for the boy they called “Putha” — son.

Inside, Wilson Uncle sat in his father’s old armchair, the same chair the elder had once puffed on cigars, sending round clouds of smoke drifting to the ceiling. Denzil settled onto a stool beside him and began flipping through the SRI magazines. They were always in landscape format, oddly shaped but beautifully printed. Each cover featured a woman, always smiling, always adorned with a flower in her hair and a jacket like she was going somewhere important.

Inside, there would be a short story — or sometimes a poem. Most often, it was Wilson Uncle’s name at the bottom.

“Uncle, this is a great story,” Denzil said.

“Yes, Putha,” came the reply, half-smile playing across Wilson’s lips. “That one I wrote in a hurry.”

Another magazine from the stack yielded a poem. Denzil’s eyes skimmed over it. He had never been one for poetry — something about the rhythm eluded him; the rhyming made him impatient. He wanted meaning, not meter. But still, he always made it a point to notice, to mention.

“There’s a poem here, too,” he said, holding it up.

Neeta Aunty had returned with another pile — Gnaththa Pradeepaya, the weekly from the Catholic Press in Colombo. In each issue, another of Wilson Uncle’s poems appeared. Denzil scanned them, glancing over the lines rather than absorbing them. He couldn’t help it. Poetry, for him, remained a kind of decorative writing — something beautiful but distant, like the painted glass windows of the church, which he rarely visited.

Still, he read. And they watched him read.

And in that quiet room, where old magazines were stacked like relics and photographs told stories without sound, it was enough.

Wilson Uncle, some 34 years later in 2005

Comments

Post a Comment