The 261 to Wattala

The 261 to Wattala

Morning Ride to School

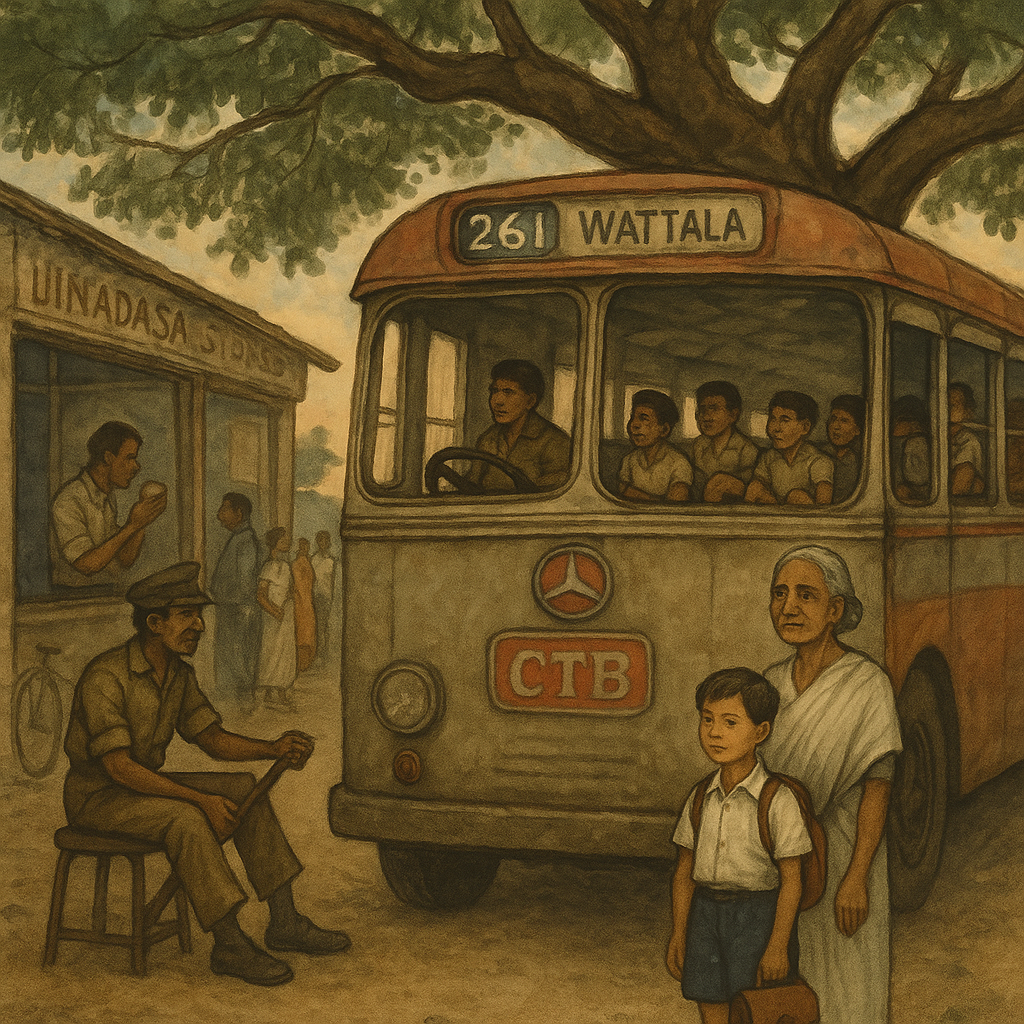

The 261 to Wattala, scheduled to leave Mahara Junction at half-past seven, arrived early, as it always did, not with urgency, but with the unhurried certainty of an old friend who knows the morning rhythm better than any clock. It stood idling under the old jack tree near Jinadasa Stores, its metal body dulled by a permanent skin of dust. Not road dust, but the kind that settles over time and refuses to leave. The Mercedes-Benz emblem on its nose had long since lost its pride. What stood out was its red CTB emblem. Marking it is run by the Ceylon Transport Board. Sun, rain, and countless fingers had worn it smooth, less in reverence than in repetition.

The St. Anthony’s boys, led by Christo, had already taken up their thrones. Brown limbs draped over cracked rexine seats, their schoolbags slouched beside them like tired dogs. They were noisy and not quiet in that way only schoolboys can be when they have already said all they need to add with their elbows and glances.

The driver, lean and the colour of dry earth, wore a once-stiff khaki that had softened like old linen with shiny silver buttons. The conductor, keeper of the rainbow ticket roll that hung like a secret, had slipped into Jinadasa’s. They sipped plain tea from chipped tumblers from behind the glass, their eyes on each other, not the time. Their mornings were not measured in minutes, but in sips and stories.

Outside, the grown-ups waited. Men with white shirts tucked in with care, trousers creased with optimism and village men with their striped sarongs Women in sarees with hems lifted neatly above the ankle, firm-footed and efficient. They didn’t stand too close to each other or to the bus. They looked down the road, not in hope, but for something rarer — assurance. A thing that neither buses nor mornings could truly offer.

I stood among them, not alone. Kadayamma stood beside me.

To the world she was “Achchie” aka grandma. But to me, she was the very sound of home. My childhood’s scent, silence, and discipline wrapped in that one word. She smelled of talcum and turmeric, of betel leaf and early rice. Her presence calmed the disorder in the day.

At 7:35, the bus wheezed into life. The driver spun the massive wheel with his hands, toes calloused and gripping like roots. His sarong was hoisted high, knees out, ready for battle. I boarded first, and then Kadayamma, he way she always did — with assurance from a thousand identical mornings. She bought our tickets: ten cents for her, five for me — one yellow, one green. The numbers ran like tiny fences across the paper. The conductor, part priest and part magician, circled our destination with a quick flick of his thumbnail.

Near the driver sat a huge metal box, the size of a big sofa, filled with something unseen, something felt more than known. The diesel engine lived there, and it roared like a lion. The gear beside it was prehistoric in size, a lever and a brown knob from another century.

I had the corner seat. The best one. Through the window, the morning unfolded like a film on slow reel — houses waking up, children on bicycles, women with bundles on their heads, fields pale with dew and early rice.

At a junction, the bus paused. I looked out and saw Kirimatiyagara church — white, still, and timeworn. My grandparents had once stood there, side by side, vowing themselves to a future that had led, somehow, to me. They were younger then. They had no bus tickets to carry — only each other on a bullock cart. Into the bus, Titus and K A D Lakshman got in, and Titus was with his mother. Lakshman travelled alone.

We passed Dalupitiya junction. Passed Kurukulawa road. People got in. The bell rang — ting-ting — and the bus pulled away like a reluctant ox.

At Enderamulla, we passed the cemetery. On the left, the Buddhist side, with garlanded poles and half-wilted flowers from recent sorrows. On the right, the Christian ground — neat, etched in crosses and saints. There was even a rest stop in between, where the living waited while the dead kept silent.

Further down, St. Sebastian’s Church rose up, whitewashed, flanked by sleepy shops. A road ran beside it, full of cyclists, early risers. The day stretched forward. Richard got in with his brothers and only sister.

At Akbar Town, a few Muslim boys climbed in. I recognised one — Ahamad with a white cap. He grinned and sat behind me, already mid-sentence. The way friends do when no greeting is needed.

Then came Hunupitiya junction. The railway line sliced across the road like a memory. The bus paused again. A brown diesel train, sighing and solemn, passed us heading towards Colombo. We got down there.

This was where our walk began — Averiwatta Road.

Kadayamma took my bag without a word. Ahamad walked beside me, his chatter a background hum. We walked on the right side of the road. Always the right side. Kadayamma’s rule.

We passed Rohan Vincent’s home. His father’s car, a black Morris Minor, stood beneath the portico. Mohan’s house came next. Mohan and his brothers joined us. Our procession grew — boys in neat uniforms, caretakers trailing behind. I looked back and saw a crowd of children and guardians in a file. Some followed the rule of the right. Half didn’t.

Premalal and his brother joined, too. Then came Indunil’s home, which looked like a shop but wasn’t. A pomelo tree grew in front of it, always bearing big fruits. Then Stanley’s place, its front shuttered like a sleeping market stall.

And finally, the school gates.

Kadayamma didn’t stop at the gate. She came in. Walked up the stairs with me. To my class.

And then she left.

Like the bus.

Like the morning.

Like all good things that know when to go.

Comments

Post a Comment