The Man with the Bicycle

The Man with the Bicycle

A Godfather Without English

Sothis fellow, Wijetunga, arrived one humid afternoon in Warakanatte – a name given by the government, clipped from some dusty file in a distant ministry, and pinned onto our village like a misfitting badge. He came not with fanfare, but with the tiredness of a man who had travelled not just across provinces but across unspoken expectations. The new Grama Sevaka – government-appointed village functionary, dispenser of forms and permits, arbitrator of neighbourly disputes, and authoriser of rice ration books.

He hailed from Enderamulla, a place that stirred vague murmurs among the older women in our family – whispers of ancestral ties, of some great-uncle’s cousin’s child from that neighbouring village. But no one invited him for tea. No one mentioned him at the dinner table as anything more than “the new man in the office.” Despite the murmurs, he remained a stranger- neither embraced nor excluded- a man who had arrived with a designation, and little else.

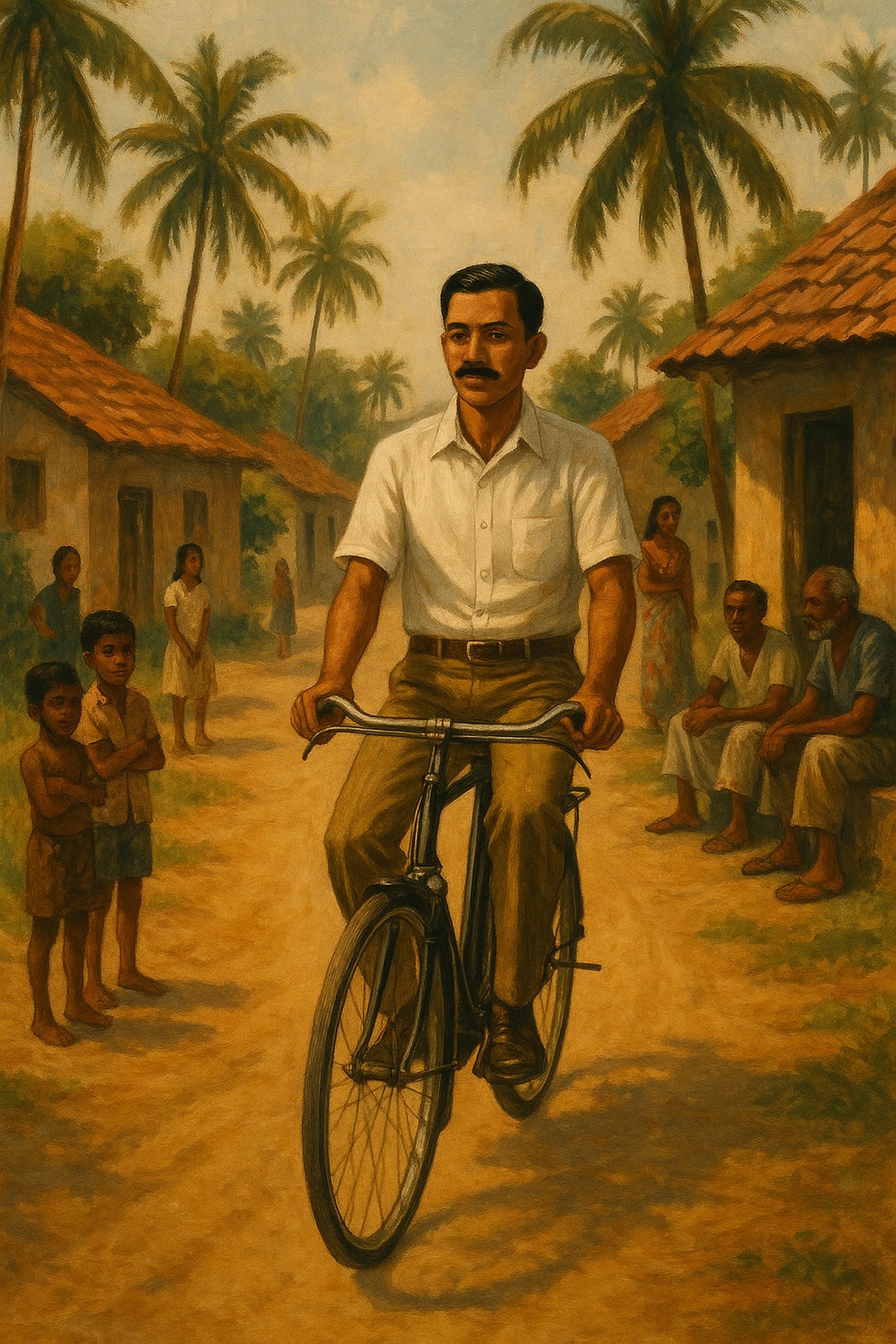

He lived in the squat little room tacked onto the side of the government office – concrete walls that refused to cool, a single window that opened with arthritic reluctance, and only to disappointment. The Kohalwila road ran beside it, sending dust in with every occasional car. His mornings began with the whine of his Raleigh bicycle – tyres gripping gravel, spokes ticking out their private metronome. The sound became familiar to us. Predictable. Like prayer bells from the temple, or the bread seller’s horn.

He had a precise pencil moustache that might have been drawn with a compass, hair that curled rebelliously but held together by oil, and trousers with buckles that made soft clinks when he walked. He was oddly meticulous, as if even his simplicity had been ironed and folded into neat lines. He was not a man who called attention to himself, yet the village always seemed to know exactly where he was.

Ten years ago, the words Grama Sevaka would have conjured something altogether different. Not just a title, but a bearing, a stature – the Vidane, the Ralahamy. The man who wore both the weight of the government and the inherited gravity of custom, balanced like twin pots on a village woman’s head. The headman.

Men like Baralan Costa, who lived just a few doorways down from us, though to speak of mere proximity was to ignore the invisible distance his presence created. He walked not in haste, but with an unhurried deliberation, as though the minutes themselves dared not pass him without permission. His sarong was always folded with geometrical precision, slicing diagonally across his belly like an insignia. His coat – hopelessly dark and tight for the tropical sun – clung to his frame with stubborn pride. And always, the black umbrella, vertical and unwavering, like a magistrate’s staff – or a relic from a time when authority was not begged for, but worn.

When Baralan Costa passed by, the street seemed to rearrange itself. Conversations paused mid-sentence, gossip lowered its voice to a murmur. Even the mongrels, sprawled lazily under the shade of mango trees, sensed the change and sat up, ears alert. No one used his name – it felt too personal, too informal. To us, and to everyone, he was Ralahamy. Nothing less.

But then, things began to change. Authority no longer looked like Cabral. It arrived on a Raleigh, wore trousers, didn’t carry an umbrella. Wijetunga wasn’t trying to be better or above anyone. He was, in fact, trying not to be. But the times were shifting. Ceylon – still answering to that name – was shrugging off its borrowed garments. British rule had gone, but its shadow lingered in post offices and police stations, in starched collars and inherited manners.

And yet, here was Wijetunga. He spoke no English, unlike my father who measured his words in the Queen’s syllables. But Wijetunga had discipline. A kind of quiet nobility in work. He did not curry favour, nor did he create distance. He did his job. He sat in his little room, wrote in ledgers, issued permits, allocated house numbers, and arranged rice ration books like sacred offerings. He treated villagers not as subordinates nor supplicants, but as people. It was radical, really, in its modesty.

Perhaps that was why my father, ever cautious in choosing friends, found an affinity with him. And when my younger brother was born – his third child – it seemed the most natural thing for my father to ask: would Wijetunga be the godfather? Wijetunga accepted with a quiet nod. Alongside him stood Aunty Helen, our extended family’s beauty, the undisputed unmarried queen of our neighbourhood, a rare woman who was fluent in English. Together, they stood at the altar – a new pairing of tradition and transition.

It was a small gesture, perhaps. A name in a register. But it said everything about where we were headed. The British were gone. Their rituals, still shadowing us, were being nudged aside by new forms. The godfather was a man without English but with integrity. The godmother was a woman known more for her beauty than her lineage and English.

He wasn’t a frequent guest in our home. He didn’t linger over cups of tea or ask after our schooling. But we knew him. We watched him. We listened for his bicycle bell. And then came Teckla.

Teckla of the rhythmic walk. Teckla whose hips had their own quiet following. Teckla who worked in a government office in Colombo and boarded the bus each morning like a commuter queen. She was beautiful in the way that made the old women purse their lips and the young boys forget what they were carrying. Wijetunga, with all his unremarkable grace, married her.

So life unfolded. Wijetunga pedalling to his duties, Teckla boarding the bus. He, immersed in census forms and disputes over coconut boundaries; she, gliding past church toward the capital. Together, they were a portrait of Ceylon in transformation – modest, shifting, uncertain – but moving nonetheless.

And it was Wijetunga, years later, who arranged for my national identity card when I crossed the quiet, uncelebrated threshold of eighteen. The photograph was taken in his office – by now no longer the hot concrete room beside the Kohalwila road, but Teckla’s front room in her father’s old house, where she had gently but unmistakably taken control of the space. The identity card was a new thing then, a novelty of the State – issued a year or two after I had technically become eligible – and holding it in my hand felt oddly permanent, like being inked into the fabric of a country still trying to define itself.

Comments

Post a Comment