A Young Rebel in Colombo

A Young Rebel in Colombo

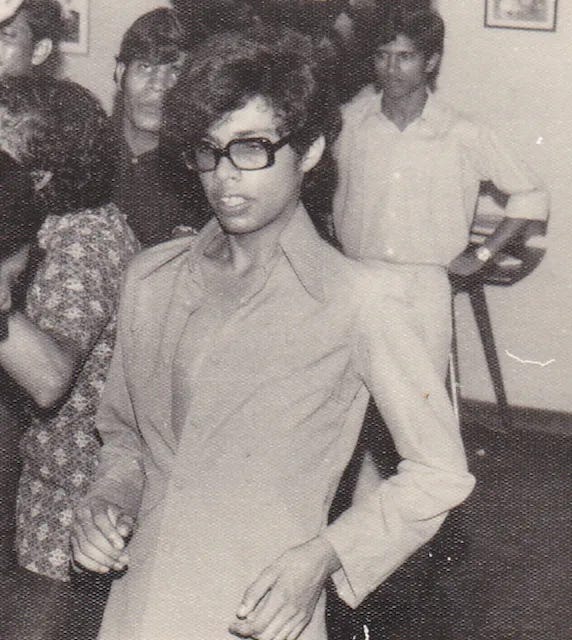

Back in the sultry summer of 1974, when I was a lad of nineteen, all legs and no whiskers, I found myself stepping into the humming world of the Overseas Telecommunication Service (OTS) in Colombo. It was my first job, a curious chapter in a life that would soon take me far from the shores of my island home. Looking back, I chuckle at the memory of those days, so full of mischief and defiance, and yet, they shaped me in ways I could never have imagined. Let me take you there, to a time when I was young, naive, and brimming with a restless spirit.

A New World of Wires and Words

The OTS building stood tall in Colombo, a fortress of clattering teletypewriters and the hum of international messages as they crisscrossed the globe. After finishing my apprenticeship, our instructor, Shirley Silva, led us, twenty-five eager graduates, up to the Instrument Room. I was the youngest, a skinny boy who looked younger than my years, with a mop of hair and a heart full of dreams. The pay was 350 rupees a month — about $85 in those days — a princely sum for a lad like me.

Carl Schokman, the chief supervisor, greeted us in his khaki shorts and knee-high socks, looking like he’d stepped out of a colonial postcard. His spectacles glinted as he spoke of our sacred duty to keep Sri Lanka connected to the world. The Instrument Room was a marvel: rows of telegraphists, all men, hunched over machines that chattered like mechanical birds. Some welcomed us with warm smiles; others sized us up with narrowed eyes. When Schokman left, a senior telegraphist bellowed, “Yako buggers!” — a crude jab meaning uncultured louts. My batchmates bristled, but I, the cool-headed kid, shrugged it off. To me, the real bogan was the one shouting.

The Rhythm of the Instrument Room

The Instrument Room never slept. It ran round the clock, with four six-hour shifts slicing up the day: 8 am to 2 pm, 2 pm to 8 pm, 8 pm to 2 am, and 2 am to 8 am. Six days a week, thirty-six hours total, with Sundays reserved for overtime and lighter loads. Half our time was spent punching messages into Baudot-Murray tapes on teletypewriters, readying them for transmission. The other half, we manned the network exchanges, connecting Colombo to far-off places like London, Tokyo, Mumbai, Singapore, Aden, and Yangon. On a typical day, we handled 1,400 outgoing messages and 1,000 incoming ones, as well as 600 to 800 transit messages passing through Colombo. Thirty of us shared the load.

In the Traffic Room nearby, six senior telegraphists — Traffic Officers — kept meticulous records of messages, word counts, and destinations, chasing Gold Francs to bolster the nation’s coffers. Five peons, the unsung heroes, shuffled messages and tapes between desks. One lad, Adhipathi, ruled the building’s only lift, perched on a stool by the buttons like a king guarding his throne. The peons who could read English became sorters, allowed to wear long pants — a small step up in a society rigid with hierarchy. The rest wore khaki shorts, a badge of their place.

The Telex Room, a glass-walled and exclusive space, housed the senior staff, while a public telex bureau operated on the ground floor. The Workshop, where technicians mended faulty machines, buzzed with a faint air of superiority. Upon the second floor, the control room — a mysterious data centre — was off-limits to ordinary folk like me. English was the language of the place, and I wielded it with ease, chatting with everyone from supervisors to peons without a care for rank.

The supervisors were a mixed lot. Gamlathge, nicknamed Dracula for his stern, Christopher Lee-like demeanour, rarely cracked a smile. Candappa shuffled in rubber slippers, his oily charm unmistakable. Wijemanne, always pristine in white, had a warm grin. Brian Lutersz, soft-spoken and bespectacled, hid his vitiligo under long sleeves. Elmo Pereira, the chief supervisor’s enforcer, typed memos with a scowl, unimpressed by my carefree ways. Mohamed Farouk was kind, and Kingsley Pandithakoralge was a kindred spirit who understood me. Roy in the Telex Room never shied from a chat.

The workforce was a tapestry of Sri Lanka’s diversity — Sinhalese from the south, Tamils from the north and east, a sprinkle of Muslims and Burghers. But women? None, save for Carmen, the telephone operator, in a place where 24/7 shifts and an unsafe city kept them away. OTS was a man’s world, steeped in hierarchy and seniority, where some seniors forgot they’d once been juniors too.

A Rebel in Bell Bottoms

I was a teenager with a job, but my heart wasn’t in it. At nineteen, I lived for the weekends — dance parties, beach trips, and mischief with friends. My wardrobe was a riot of bell-bottoms, jeans, and colourful singlets, a stark contrast to the starched shirts of my colleagues. I didn’t care for office norms; I was the odd lad, daring to be different.

The work was easy enough. Between messages, I read books, tossed paper balls, and made my batchmates laugh. I was also a part-time student at Aquinas University College, where I studied accounting. Juggling day shifts, evening classes, and my social life was a losing battle. I chose parties over textbooks, abandoning Accounting that year.

Overtime paid a measly six rupees for six hours — a quarter an hour. I traded my extra shifts for day ones, freeing my evenings for friends and fun. Two batchmates asked me to be their best man at their weddings. At nineteen, I donned my first suit—tailored for 350 rupees—and stood proudly by their side, wondering why they’d chosen a skinny kid like me.

A Strange Friendship

In the Instrument Room, a senior named Dharmapala took a shine to me. He was older, bearded, and smoked vanilla cigars. He arranged my shifts, trading my overtime for day shifts so I could keep my evenings free. We’d have lunch at city restaurants, but we were an odd pair, with little in common. Then he overstepped, visiting my parents and telling them I smoked — a gross exaggeration. My father, a liberal soul, brushed it off, but my mother was livid. That was the end of his home visits.

Dharmapala grew controlling, meddling in my work and friendships. I snapped, confronting him and ending our strange alliance. He tried to win me back, but I stood firm, my independence non-negotiable.

The Firecracker Rebellion

The OTS was a place of petty politics, where seniors wielded power over juniors. Messages sent over aging underwater cables often arrived garbled, and some seniors used these errors to harass those they disliked. I received countless memos for minor mistakes, which I ignored. The place felt stifling, and I knew I didn’t belong.

With my new batch of juniors, I started a quiet rebellion. We replied to memos in Sinhala, knowing Elmo Pereira couldn’t read it. We signed logbooks in Sinhala too, forcing him to find translators. It was our way of poking the bear.

Then came the Sri Lankan New Year in April. In my village, we lit firecrackers under buses, laughing as drivers scrambled to check their tires. Inspired, I smuggled a firecracker into the OTS, rigging it with a thread to go off in an empty corner. At 1 pm, I lit the thread and slipped away. The bang echoed through the building, sparking chaos. Some thought the air conditioner had exploded. Elmo Pereira led the investigation, grilling me for an hour, but I didn’t crack. They couldn’t pin it on me, but I was a marked man.

The Non-Aligned Summit and Union Defeat

In August 1976, Colombo hosted the Non-Aligned Summit, a grand gathering attended by eighty-five heads of state. OTS was at the heart of it, with a new Russian satellite boosting our capabilities. My colleagues worked the event, but I was sidelined as a troublemaker. Furious, I channelled my anger into the upcoming union elections. We rallied behind a junior leader, but the seniors crushed us at the polls. Still, we’d rattled their cage.

A Naked Dare

Not all my moments were rebellious. One evening, after a shift, I joined some friendly seniors on the seventh floor for drinks. They dared me to take off my pants. Having skinny-dipped in boarding school, I didn’t hesitate. I stood there, all 47 kilos of me, and they roared with laughter. It was a moment of youthful bravado, and I owned it.

The Final Straw

Night shifts were torture, cutting into my social life. One night, after a 2 am finish, I walked 1.5 kilometres to Pettah’s bus stand, dodging shadows in the dark, to catch a bus home. Another time, a garbled telegram from France sparked a media frenzy, with OTS labelled incompetent. I’d signed off on the message, making me an easy target. An investigation cleared me — the error was London’s — but the ordeal left me disillusioned.

Breaking Free

I knew I had to leave. I applied to a foreign bank in Colombo and also considered Nigeria, but I received no offers. Then, out of the blue, Dubai called — a city barely known in 1976. I broke my five-year bond with OTS, my father covering the cost, and left Sri Lanka in ten days. I was the first from OTS to venture to the Emirates, a pioneer in my small way.

Epilogue

In Dubai, I found freedom. Many OTS colleagues followed, including Elmo Pereira and his wife, Rhona, with whom they became dear friends. Over meals and drinks, we laughed about the past, equals at last. Within a year, I earned more than my old supervisors, a quiet triumph for a rebel kid.

That brief stint at OTS taught me to dare, to dream, and to defy. It launched me into a career across three continents, leading teams in global financial firms. I’ve mentored over a hundred young graduates, watching them soar, and I live a life unbound by class or convention. My youthful rebellion wasn’t just folly — it was my redemption.

Comments

Post a Comment