A Schoolmaster’s Retreat

A Schoolmaster’s Retreat

Finding Freedom in a Faraway Village

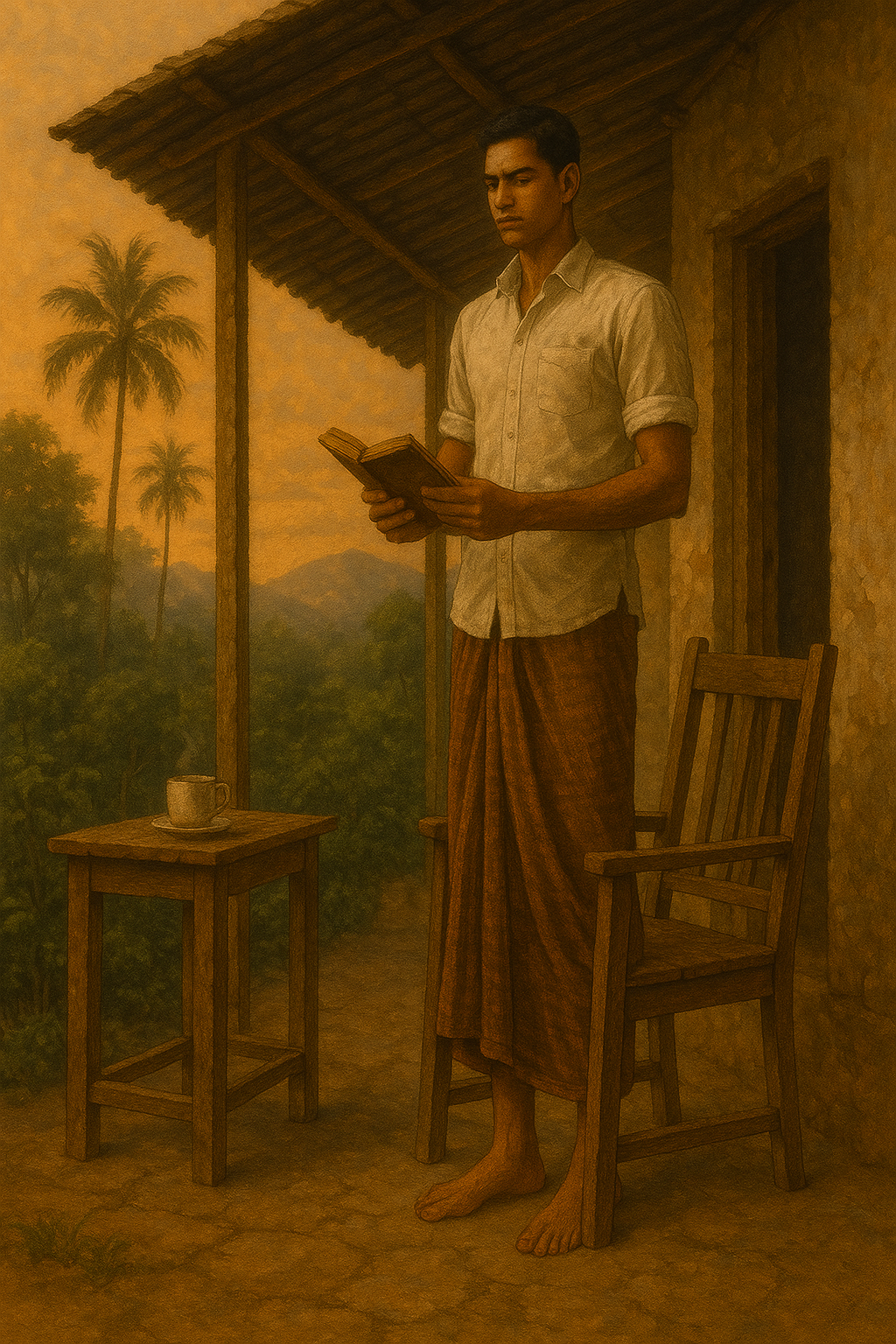

The monsoon had been late that year, and the red earth around Dedigama cracked like old leather in the heat. From his veranda at the government school, John Christie Jayawardane watched the children walk home in the shimmering afternoon, their haphazard uniforms bright against the bushes that cascaded down the pathways like green waterfalls.

Six years he had been here, six years since he’d taken the bus up from Kadawatha with nothing but a fake leather satchel and a determination to disappear into a far-away village. At thirty, he had achieved something remarkable in a society that measured a man’s worth by his family obligations and properties: he had become nobody’s responsibility and responsible for nobody.

The telegram that changed everything arrived on a Tuesday, carried by young Bandara, who was the postman in the village below. The boy’s face was grave as he handed over the brown envelope, understanding without words that telegrams rarely brought good news to schools and other government offices where people came to escape the world below.

Father passed yesterday, stop funeral Thursday, stop come immediately, stop Susan

John Christie read it twice, then set it down beside his evening tea. Through the window, he could see the sacred mountain of Adam’s Peak in the distance, its distinctive silhouette unchanged by human sorrows. He felt something shift inside him — not grief, exactly, but the recognition of a door closing somewhere in the geography of his heart.

His father had been a school principal in the Education department, one of those Ceylonese who had learned to navigate between the old world and the new. When independence came in 1948, men like his father had found themselves caught between the departing British and the rising Sinhalese nationalism, speaking English and Sinhala, belonging fully to neither world.

The bus journey to Kadawatha felt like travelling backward through time. The cool air of the country gave way to the humid embrace of the lowlands, and with each mile, John Christie felt the weight of family expectation settling on his shoulders like his father’s old white suede coat — familiar, suffocating, inevitable.

The house in Eldeniya looked smaller than he remembered, its red-tiled roof and whitewashed walls dwarfed by the fence around it. Susan met him at the gate, her face drawn with the particular exhaustion of someone who has been making arrangements for death. Behind her, Thomas hovered with the uncomfortable air of a man who married into problems he hadn’t anticipated.

“The aunties have been asking about Mother,” Susan said without preamble. “What arrangements do you make?”

Their mother sat in the front parlour, expressionless and dressed in white cotton as if she were already a widow preparing for her departure. The doctors called it mental sickness, but John Christie preferred to think of it as a strategic retreat into a country where other people’s expectations couldn’t follow. She embraced him with a big smile and interest one might show a lost child, her mind having long ago released its grip on the uncomfortable business of remembering.

The funeral was held at Holy Mother of Expectations Church, that sturdy stone monument to colonial Christianity that stood like an uncomfortable reminder of Ceylon’s complicated history. The service was conducted in Sinhala, and most of the mourners whispered their prayers in Sinhala. Father Vincent Dep, who had known the family for decades, spoke kindly of duty and service, his voice softened by twenty years under the tropical sun.

Afterwards, the relatives gathered like crows at a feast, each with their own opinion about what should be done. The house would need to be occupied, they said. Mother would require proper care. Catherine, poor child, had spent too many years tending to her father and needed a husband found for her before she remained too long single.

And John Christie, as the eldest son, would naturally assume his proper role.

He listened to these pronouncements while standing beneath the portrait of his father that still hung in the dining room, a relic in their house. The gentle irony of his situation would have amused him if it weren’t so close to home. Here he sat, surrounded by well-meaning relatives who spoke earnestly of duty and tradition, their voices rising and falling like the drone of cicadas on a summer evening. Behind them, his father’s framed photograph gazed down from the wall — the stern but kindly face of a man who had spent forty years shaping young minds as a school principal, who had earned the quiet reverence that comes to those who serve their community with patience and grace.

Yet even that beloved image seemed to shimmer with uncertainty, as if the glass were trying to reflect not just a man’s face, but the weight of expectations that had died with him. What did it mean to belong to a family, to a place, to a way of life that felt as foreign to him as the customs of distant lands? The old house, the Jayawardane family home itself, seemed to be asking the same question, its walls holding memories that belonged to everyone except him.

John Christie found himself caught between two worlds — the one that claimed him as its own, and the one where he had learned to breathe freely among strangers and paddy fields that asked nothing of him but his presence.

“I’ll visit on weekends,” he announced, the words falling into the discussion like stones into still water.

The silence that followed was profound. Aunt Agda, his father’s sister, adjusted her long skirt with the precise movements of someone preparing for battle.

“Visit?” The word emerged from her lips as if it tasted bitter. “A son doesn’t visit his obligations, John Christie. He fulfils them.”

But he had already made his choice, standing there in that parlour with its mixture of colonial furniture and traditional brass lamps. The village was calling him back with its promise of anonymity, its gift of letting a man become precisely as much or as little as he chose to be.

The weekend visits became a ritual of careful distance. He would take the afternoon bus from the Dedigama bus stand, arriving at dusk when the frangipani trees released their evening perfume into the cooling air. The house felt like a museum of his former life, filled with objects that belonged to someone he used to be.

Catherine drifted through his weekend visits like morning mist taking shape, her presence soft and uncertain, as if she were still deciding whether to fully appear in the world or fade back into the familiar shadows of the old house. She would serve him tea without being asked, her movements economical and precise, as if she had choreographed her invisibility. Their conversations were archaeological expeditions into the possibility of connection, each attempt revealing only more layers of unfamiliarity.

“The roof leaked during the last rains,” she might say.

“You should have Jeramius look at it,” he would reply, already planning his return to the village where such problems belonged to landlords and headmasters, not to him. Jeramius was their cousin and manservant.

In the village in Dedigama, his absence became part of the local mythology. The children he taught would go home with stories of their mysterious schoolmaster who appeared and disappeared like a character from the Jataka tales. Some said he was a man who had renounced the world without becoming a monk. Others whispered that he had loved unwisely and chosen solitude over heartbreak.

The truth was simpler and perhaps more scandalous: John Christie Jayawardane had discovered that he could be happy alone, that society’s careful architecture of obligation and duty was not the only way to construct a life. In 1962, in a Ceylon still learning how to be Sri Lanka, this was a form of rebellion as quiet and complete as independence itself.

His monthly salary of one hundred and seventy-five rupees arrived with the regularity of the monsoons. It was enough for his small room overlooking the small houses, his meals at Gunadasa’s cafe where the village cook prepared hoppers and fish curry that reminded him of his grandma’s cooking from childhood, his books ordered from the M D Gunasena’s bookstore in Colombo.

Sometimes, lying in his narrow bed and listening to the night sounds of the fields — the distant call of a fox, the rustle of small creatures in the thatch above, the whisper of wind through the banana bushes — he would compose brief letters to his family. In these mental compositions, he was eloquent about duty and love, generous with promises of support and care. The words formed perfectly in his mind, noble and reassuring as a Dharma sermon.

But morning would come with its gift of forgetfulness, and the letters remained unwritten. Instead, he would walk to the school in the pearl-grey light of dawn, his footsteps joining the ancient rhythm of a world that asked nothing of him but his presence, offered nothing but the profound peace of anonymity.

By October of 1962, Susan had made her peace with her brother’s choice. Standing in her expanded house, Thomas had used his savings to add two rooms for Catherine. She watched her children play in the garden and understood something about the different ways people could choose to love their families.

Some loved staying. Some loved to leave. And some, like John Christie, loved by becoming so thoroughly themselves that they offered the gift of absolute honesty to a world too often built on the comfortable lies of obligation.

In the hills above Ceylon’s coconut country, where the British had once retreated from the heat of empire and the Sinhalese kings had once hidden from invasion, a schoolmaster had found his form of refuge. Each morning, as he rang the bell that called the children to their lessons, John Christie Jayawardane participated in the quiet revolution of a man who had learned to answer only to himself.

The mountains, indifferent and eternal, approved.

Comments

Post a Comment