Trousers and Trails

Trousers and Trails

A Boy’s Odyssey in 1970s Ceylon

InCeylon of 1971, when I was a lanky sixteen-year-old, all sharp elbows and restless dreams, I longed for long trousers — the kind that spoke of manhood, leaving behind the tattered shorts of boyhood like leaves shed in a monsoon wind. My pockets were as empty as the sky before the rains, not a rupee to spare for cloth or a tailor’s craft. So, I turned to my uncle’s old trunk, pulling out a pair of his trousers — sturdy, weathered things, shaped for a man of forty with a life broader than my own. I took them to Prince Tailors, a shadowed nook in the bazaar’s pulsing heart, where the old tailor, his spectacles glinting like twin moons, handled the fabric as if it whispered tales of forgotten years. Those trousers, cut for a grown man’s frame, draped over me like a scarecrow’s cloak, flapping about my skinny legs. The tailor worked his quiet magic, but my dreams of flared bell-bottoms, bold as the heroes in crumpled film magazines, were beyond his simple skill. The fly, absurdly long, seemed to mock my youth, yet I wore them with a stubborn swagger, as if I could fool the world into seeing me as more than a boy teetering on the edge of something grander. A whisker or two had begun to shadow my upper lip — tentative signs of manhood — and with them came a quiet, unspoken confidence. It was not just the trousers that made me feel older, but the subtle thrill of transformation blooming on my face.

But this isn’t just a tale of those borrowed trousers or the fleeting vanities of youth. It’s about the journeys that threaded through our family’s days, woven across the green hills and sun-dappled plains of Ceylon, stories richer than any pair of pants could ever hold. The first was to Bandarawela, in a red government-issued hatchback, tough as an old buffalo, driven by Cooray, my father’s driver. For us — my mother, my sister, my little brother, and I — it was a holiday, a chance to break free from the humdrum of home. For my father, it was work, bound for an all-island conference, a grand gathering of councillors, mayors, and secretaries, their voices heavy with the dreams and duties of a young nation.

The red car rolled up to our gate, its engine purring like a restless cat. My father and Cooray took the front seats — no seat belts in those carefree days, just trust in the road’s goodwill. In the back, a space meant for three small souls, my sister, my little brother, and I squeezed tight, leaving just enough room for my mother, all four of us pressed close in that rattling cocoon. It was my moment to wear my black trousers, those ill-fitting badges of my imagined maturity. As the car wound through the emerald hills, where tea estates stretched like a quilt sewn by giants, I sat taller, the trousers a silent promise that I was stepping into a larger story, one leg at a time.

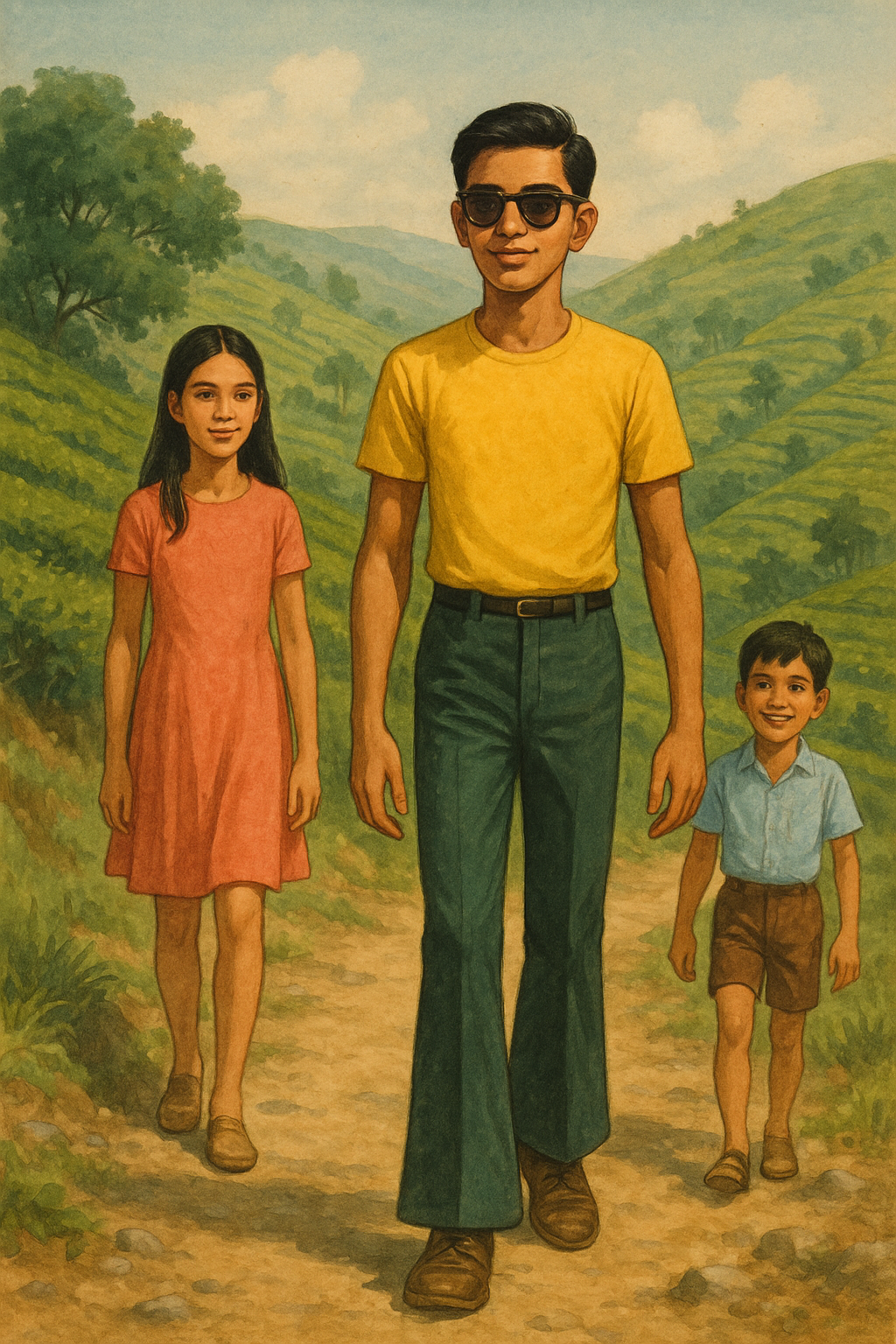

After eight hours of driving, the road curling through mist and memory, we reached Bandarawela, where the conference buzzed with purpose. Chairmen, mayors, and their senior public servants gathered, their families trailing like cheerful shadows. The women, the wives, the children — all were welcome, their laughter weaving through the air. We were housed in a rambling holiday home, our family tucked into a single large bedroom, its walls creaking with the secrets of past guests. But it was the afternoons I loved best, when, as the eldest, I’d lead my siblings — my sister, twelve, and my brother, eight — on wanders through the hilly country. The rickety roads wound through tea estates, where leaves shimmered like green stars under the sun. I’d sneak my father’s Ray-Ban sunglasses, their thick black frames lending me a borrowed air of grandeur. With those sunnies perched on my nose and my trousers flapping about my legs, I felt larger than life, a young prince of the hills, leading my siblings down streets that unfolded like pages in a book of wonders. The wind carried the scent of tea and earth, and in those moments, I was no mere boy in oversized clothes — I was an adventurer, a storyteller, a brother guiding the way.

The next year, 1972, brought another gathering, this time in Trincomalee, on Ceylon’s northeastern shore. The council’s car was claimed by the chairman, so my father, ever the holiday spirit, refused to let work eclipse family adventure. We packed — my parents, my sister, my brother, and I — and set off by train, a rattling, ten-hour journey across the island’s heart. I’d managed to coax my mother for enough money to buy two lengths of cloth — one dark brown, one dark green — and returned to Prince Tailors. The old tailor, delighted I’d brought fresh material instead of hand-me-downs, set to work. This time, the chief tailor stitched me proper bell-bottoms, high-waisted and bold, just as I’d seen in the glossy pages of magazines. For the trip, I wore the dark green pair with a bright yellow T-shirt, the brown trousers folded carefully in my bag, a promise of swagger to come.

The train ride was not without its dramas. An overhead bag toppled onto my little brother, startling but not harming him, and we laughed it off as the carriage swayed through the night. At Trincomalee’s station, we were herded to a shared holiday home near the beaches, where families like ours — children, parents, fathers in politics or civil service, mothers in sarees — filled the air with chatter. Some men wore shirts and trousers, others vettis or arya sinhala, while the children sported shirts, shorts, or frocks, a merry patchwork of Ceylon’s many faces.

In between the conference’s hum, we explored. At Seruwawila temple, a mischievous boy jabbed my brother with a pencil, sparking my mother’s wrath as she scolded the culprit and his mother, her voice sharp as a monsoon gust. At Kanniya hot water temple, we bathed in the warm springs, but I was forced to change in public, without a towel shield, my teenage cheeks burning with embarrassment. Koneshwaram temple, perched on a rock by the sea, was a place of ancient reverence, its stones whispering of pilgrims long gone. Yet, for all the mishaps, those days glowed with adventure.

The brightest thread of that trip was meeting Athula Karunaratne, the son of a minister and chairman of the Rakwana council. Athula, a student at Ananda College and the only other boy in long trousers, became a fast friend. We bonded over shared dreams and the thrill of feeling grown-up, meeting later in the canteen by his father’s ministry, swapping stories until I left Ceylon years later. In those moments, with my bell-bottoms swaying and the sea breeze in my hair, I wasn’t just a boy from a small island — I was a wanderer, a friend, a keeper of stories, with Trincomalee’s shores and Bandarawela’s hills etched forever in my heart.

Written by Denzil Jayasinghe

Lifelong learner, tech enthusiast, photographer, occasional artist, servant leader, avid reader, storyteller and more recently a budding writer

Comments

Post a Comment