Star and Style

Star and Style

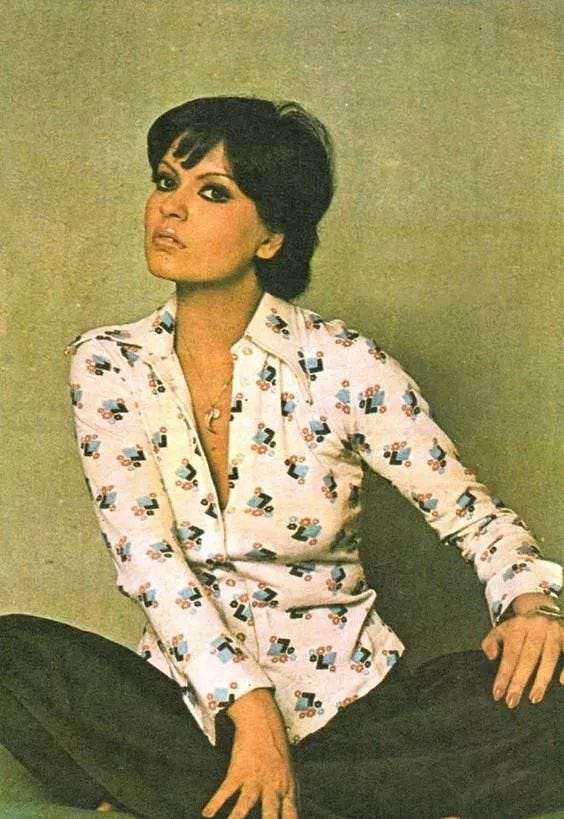

Zeenat Aman’s gaze

In the grit and bustle of Colombo, a boy’s everyday world is transformed by a glossy magazine cover. Star and Style is a portal to glamour — a promise of cinema, stars, and dreams far beyond the heat, dust, and crowded lanes. All for two rupees and fifty cents. Through his small, secret purchase, he finds not just escape, but the stirrings of wonder, longing, and the belief that another world might be waiting beyond the familiar.

The magazine was Star and Style, its cover glossy and irresistible, promising escape into a universe brighter than the heat and grime of Maradana. Across the page, in large letters, it proclaimed: “Zeenat Aman, the Style Icon.” He bought it from Hemasiri’s bookshop, a narrow shop squeezed between a tea stall with the smell of boiled milk and dusting tea leaves, and a tailoring shop where the whirr of a sewing machine spilled into the street. At the doorway, periodicals dangled from metal clips, stirring each time a bus screeched to a stop, raising little gusts of wind and dust that made the magazines sway like restless birds tethered in a cage.

On the racks he recognised Filmfare, The Illustrated Weekly of India, Stardust, and, stacked alongside, books by James Hadley Chase and Enid Blyton, as well as the daily papers — Dinamina, The Daily News, and The Daily Mirror. There was also Flip magazine, with the boy band, Bay City Rollers in their ankle pants and shaggy haircuts. He ran a hand through his own hair, wondering if his style bore any resemblance.

The shop smelled faintly of mildew, the scent of old paper that had passed through countless hands, carrying the sweat and breath of strangers. The shopkeeper, spectacles sliding down his nose, handed over the magazine with a smile free of malice — just the weary understanding of a man who had seen countless boys surrender their few rupees for fleeting glimpses of glamour. Two rupees and fifty cents: a price that stung and thrilled at once.

Out on the pavement, he tucked the magazine under his arm like a secret and merged with the crowd. Maradana moved in its usual rhythm — the hawker’s call for boiled gram, the bell of a bullock cart lumbering towards Fort, the singsong bargaining of students over used textbooks stacked like bricks of another kind of future. All of it swirled about him, yet the magazine’s presence was a private current, invisible but powerful. Every now and then he glanced at Moushumi’s inviting face, the winked eye and commanding, urging him forward as though the heroine herself had claimed him for a larger destiny.

Inside the shop, unnoticed, a boy in a frayed white school uniform still lingered among the shelves, flipping through ragged magazines, peeking at glamour he could not yet buy. He never looked at the one who had just walked out, clutching the latest Star and Style with Moushumi on the cover, as if it were a passport to a brighter universe.

He held it close, careful not to crease its edges. For those few coins spent, he had purchased not merely a magazine but the promise of another world — one of technicolour drama, where voices rose louder than traffic, where heroes fought longer and harder than men in real life ever could in Colombo and heroines more beautiful than the actresses in local cinema.

On the 132 bus home — a British Leyland double-decker, an old London Transport relic with cracked cushion seats and a conductor weaving through the aisle, calling out in weary cadence — he opened the magazine at its first page. The city outside blurred into dust and noise while he lost himself in exclusive interviews, insider tales, and the delicious frivolities of gossip columns. There were photographs of Rajesh Khanna, Hemai Malini, Amitabh Bachchan, Saira Banu, Rekha, Jaya Bhaduri in colour. Photos from muhurats, those ceremonial beginnings of films he would never witness in person, yet felt a part of now, as though by reading he too had stood at the edge of the studio floor when an oil lamp was lit and the camera rolled on the inaugural shot.

The 132 bus lurched forward with a groan, its engine protesting as though burdened by too many lives at once. He gripped the magazine and slid into a corner seat, careful to keep it away from the grime of the window ledge. The conductor, a thin man with a red towel flung across his khaki coat, clanged his coin box and shouted the route, his voice hoarse from repetition. Passengers climbed in — office clerks with files tucked under their arms, women clutching market bags that released the faint smell of chillies and coriander, schoolboys and who clattered noisily down the aisle, their shoes caked with playground dust and the silent school girls in white uniforms with parted hair.

He bent over his magazine, determined not to let the world intrude. The glossy pages felt strange against his fingertips, so unlike the rough paper of textbooks. He turned to the interviews — Amitabh quoted about struggle, directors speculating about the future of cinema, starlets offering fragments of their private lives in rehearsed candour. He read every word hungrily, as if they contained not mere gossip but a language of aspiration, a map to a world beyond the narrow streets of Colombo.

The bus rattled through Dematagoda, Maligawatta and Baseline road, and at each stop more bodies pressed inside, until elbows jabbed and shoulders touched, but he held his Star and Style like a shield, folded close to his chest. A little girl standing beside him stared at the cover, her eyes wide at the looming figure of Mousumi and her wink on the over. He angled the magazine away, embarrassed by her curiosity, unwilling to share the magic too freely.

Outside the window, Colombo blurred past — road tracks gleaming in the late afternoon light, bicycles weaving dangerously between cars, a cow ambling along the edge of the road as though untouched by the city’s urgency. But inside, within the soft rustle of the pages, he was somewhere else: at a glittering muhurat, watching stars lighting oil lamps and smile for photographers; on a film set, where lights glared and a director’s voice called for silence.

For the price of two rupees and fifty cents, he had transformed the ride home — no longer a sweaty, crowded journey through familiar streets, but a passage into a larger world. When the bus turned towards his stop, he folded the magazine with reverence, slid it under his shirt to protect it from the jostling crowd, and stepped down to the pavement. The day’s noise closed in again — the horns, the hawkers, the crows — but within him the voices of cinema still echoed, and Moushumi’s inviting gaze seemed to follow him into the fading Colombo evening.

Images belong to the original owners

Subscribe to my stories https://djayasi.medium.com/subscribe

Comments

Post a Comment